2012 INDUCTEE - MIKE JONES

By Michael Casagrande

Decatur Daily Sports Writer

Forget sports, Mike Jones' parents just hoped their little boy would walk again. These were the years before Jonas Salk was a household name and polio still crippled children across the world. So, while the vibrant youngster living on Eighth Avenue was paralyzed for two years, his father never gave up hope. Ralph Jones laid his son flat on a table exercised his legs to keep the muscles from degenerating. Before work and during his 30-minute dinner break, the ritual continued: Keep that knee straight while pushing the young foot back as far as it would go. By the time Jones was 5, he was learning to walk again. At 6, he was running to the ball fields at Delano Park where a lifelong love affair began.

Forget sports, Mike Jones' parents just hoped their little boy would walk again. These were the years before Jonas Salk was a household name and polio still crippled children across the world. So, while the vibrant youngster living on Eighth Avenue was paralyzed for two years, his father never gave up hope. Ralph Jones laid his son flat on a table exercised his legs to keep the muscles from degenerating. Before work and during his 30-minute dinner break, the ritual continued: Keep that knee straight while pushing the young foot back as far as it would go. By the time Jones was 5, he was learning to walk again. At 6, he was running to the ball fields at Delano Park where a lifelong love affair began.

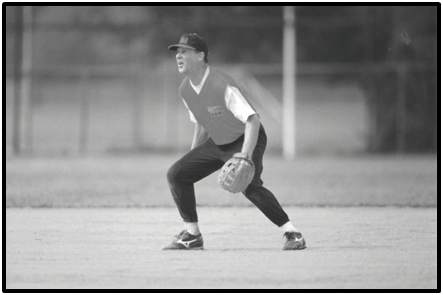

Jones, now 66, still plays baseball in a men's senior league after a long career in fast-pitch softball. Soon, he'll add another honor to his long list. One of six members set for induction to the Morgan County Sports Hall of Fame on June 9, Jones remains thankful for his father's foresight. "We just called it a miracle," Mike Jones said. "We didn't really know exactly, we just knew we needed to work those muscles and he did that. ... It was a miracle as far as we were concerned."

Through the years, Jones estimates he's played with or against 60 percent of the Morgan County Sports Hall of Famers. In fact, his polio diagnosis was made by future inductee Dr. Kermit Pitt. Jones lives in Decatur where he operates an insurance business on Second Avenue.

Through the years, Jones estimates he's played with or against 60 percent of the Morgan County Sports Hall of Famers. In fact, his polio diagnosis was made by future inductee Dr. Kermit Pitt. Jones lives in Decatur where he operates an insurance business on Second Avenue.

But his story extends well beyond the Morgan County borders. After playing baseball, basketball and football for Shorty Ogle's final Decatur High team, Jones took his talents to Tuscaloosa. A shortstop, he was excited to

play baseball for Joe Sewell, a cousin of Morgan County Hall of Famer Rip Sewell. It was 1963 and the Jones family hoped some scholarship money could help out. So a meeting was arranged with Alabama athletics director and football coach Paul "Bear" Bryant. It was a short meeting."Well, Mr. Jones," Bryant said, "We give all of our scholarships to the football players."There was a silver-lining. Sorta. "But he said, 'If he keeps his nose clean and has a good year, we might could help him with his books,' "Jones remembers hearing. "That was that attitude back then in 1963."Jones got to know a dorm neighbor named Joe Namath who liked playing baseball, too.

After that one season on the Tide freshman team, Jones returned to the area and attended an Athens State College lacking a baseball team. The plan was to return to Alabama the next year when he heard about a Major League Baseball tryout camp in Birmingham. This was before the draft and only 16 teams made up the two

leagues."So I responded and went down to Rickwood Field in Birmingham, which was sacred ground for people my age," he said. It was on top of the first-base dugout where Jones signed a contract with the Pittsburgh Pirates, his childhood favorite. "I don't think there was any money involved," Jones said. "If there was any, it was very little. But it didn't make any different. If you got a chance, you were just tickled to death."

All set for his new life in the minors, world events intervened. Uncle Sam called weeks before Jones was to report for rookie ball in Bluefield, Va. Head to Fort Benning, Ga., was the message. You've been drafted by the U.S. Army. The war in Vietnam sent Jones into the service for two years. Eventually, he landed in Oklahoma where some high-level baseball was played within the military. Jones played games with future baseball hall of famer Rollie Fingers and a young catcher who couldn't have been older than a teenager."I played against Johnny Bench," Jones said. "He was just a young ball player out in Oklahoma. Nobody knew anything about him."Jones' status with the Pirates organization also changed while stationed in Oklahoma."I never did anything with the Pirates," he said. "I never threw a pitch, never got evaluated, but got traded to Kansas City. I never understood it, but it didn't matter. You were just property."

All set for his new life in the minors, world events intervened. Uncle Sam called weeks before Jones was to report for rookie ball in Bluefield, Va. Head to Fort Benning, Ga., was the message. You've been drafted by the U.S. Army. The war in Vietnam sent Jones into the service for two years. Eventually, he landed in Oklahoma where some high-level baseball was played within the military. Jones played games with future baseball hall of famer Rollie Fingers and a young catcher who couldn't have been older than a teenager."I played against Johnny Bench," Jones said. "He was just a young ball player out in Oklahoma. Nobody knew anything about him."Jones' status with the Pirates organization also changed while stationed in Oklahoma."I never did anything with the Pirates," he said. "I never threw a pitch, never got evaluated, but got traded to Kansas City. I never understood it, but it didn't matter. You were just property."

Upon discharge from the Army, Jones was a 22-year-old with sharp skills. But 22 was ancient in baseball years at that time. There were 18- and 19-year-olds with the same ability with a longer shelf life available."So, I could see the handwriting," Jones said. "I had a lot of friends that I'd seen follow baseball around for several years, and it was very hard to get above the Double-A level. ... And I was a good player, but you have to remember, back in high school and college, baseball was a game you played until you got back to football and basketball."

So he moved back to Decatur and took up softball. Jones played high-level fast-pitch for 25 years and was inducted into the Alabama Amateur Softball Hall of Fame in 2009. He entered the West Alabama Fast-Pitch Softball Hall of Fame on May 18 in Tuscaloosa. He swapped back to baseball in the mid 1990s. Jones still plays in an adult league in Decatur with his son. Tyler Jones was a Division III All-American baseball player at Huntingdon College in Montgomery from 2002-06. So, who's better these days? Father or son? "If it were a dodge ball game, they'd probably pick me first," Tyler Jones said. "But he'd probably figure out a way to get the upper hand in some aspect of the game."

So he moved back to Decatur and took up softball. Jones played high-level fast-pitch for 25 years and was inducted into the Alabama Amateur Softball Hall of Fame in 2009. He entered the West Alabama Fast-Pitch Softball Hall of Fame on May 18 in Tuscaloosa. He swapped back to baseball in the mid 1990s. Jones still plays in an adult league in Decatur with his son. Tyler Jones was a Division III All-American baseball player at Huntingdon College in Montgomery from 2002-06. So, who's better these days? Father or son? "If it were a dodge ball game, they'd probably pick me first," Tyler Jones said. "But he'd probably figure out a way to get the upper hand in some aspect of the game."